Dielectric barrier discharge cold plasma for managing red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Herbst)

The red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), is one of the major stored products pests, causing substantial economic losses globally. The increasing restrictions on chemical fumigants necessitate the development of eco-friendly alternatives.Read more …

The red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), is one of the major stored products pests, causing substantial economic losses globally. The increasing restrictions on chemical fumigants necessitate the development of eco-friendly alternatives. This study has found the insecticidal potential of a pin-to-plate dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) cold plasma system against adult of the red flour beetle. Adults were exposed to plasma at varying voltages (15, 20, and 25 kV) and durations (30, 45, and 60 minutes) at a constant electrode distance of 9 cm with five adults per treatment. Mortality was assessed 3, 4, and 5 days post-treatment. Results showed mortality is directly dependent on voltage, exposure duration, and post-treatment time. The highest mortality (55±10.00%) was recorded at 25 kV after 60 minutes of exposure, observed 5 days after treatment. These findings conclude that cold plasma is a promising non-thermal technology for managing T. castaneum, but parameter optimisation is crucial for achieving maximum efficacy.

Tribolium castaneum, Cold plasma, Pest management, Stored products, Non-thermal technology, Eco-friendly

1 Introduction

Pest infestations in stored food products are a primary threat to global food security. Post-harvest losses due to insect pests are estimated to be between 5-15% globally, and in some regions, losses can reach up to 20-30% representing a significant economic impact on the food supply chain (Stathas et al. 2023). Among these most notorious pests is the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Herbst). T. castaneum is one of the most widespread and damaging secondary pests of various stored grains and processed food products, such as flour, cereals, and processed foods (Awadalla et al. 2023). There was an increased population growth of these pests due to their high reproductive rate and rapid life cycle, thus leading to widespread infestations. Infestations can be due to direct feeding damage, contamination with insect fragments and faeces, and the formation of mould growth, resulting in larger economic losses and quality degradation. And also, the pests can secrete some chemicals like benzoquinones, which can impart a brownish tinge and a pungent, disagreeable odour to flour, making it unmarketable. (Loconti and Roth 1953; Negi et al. 2022).

For decades, managing stored-product pests was highly relied on synthetic insecticides and fumigants. However, heavy examinations were done on the use of these chemicals due to concerns over insect resistance, harmful residues on food products, and negative environmental impacts (Stejskal et al. 2021). This has triggered research into non-chemical, physical treatment methods. Several physical treatments such as microwave (MW) irradiation and radiofrequency (RF) heating etc. were discovered for the management of these pests, but it liberates a higher heat energy at its higher treatment dosage making it undesirable effects on the food commodity. Cold plasma, regarded as the fourth state of matter, is a developing non-thermal technology having wide applications in the food processing and agricultural sectors (Thirumdas, Sarangapani, and Annapure 2015). It is actually a partially ionised gas generated by applying energy in the form of an electric field on any gas, thereby forming a rich mixture of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), charged particles, and UV photons (Chizoba Ekezie, Sun, and Cheng 2017). These reactive species are effective in killing microorganisms and insects without raising the temperature of the treated product, making it a better option for the commodities that are heat-labile (Harikrishna et al. 2023). Moreover, the insecticidal properties of cold plasma against various storage pests have been demonstrated in various studies, including Sitophilus oryzae, Plodia interpunctella, and Rhyzopertha dominica (Esmaeili et al. 2021; Madathil et al. 2021; Than et al. 2024). Recently, (Zinhoum, El-Shafei, and Elashry 2025) found the effectiveness of CP treatment on almond moth, Ephestia cautella and the saw-toothed grain beetle, Oryzaephilus surinamensis. The plasma-generated RONS dominate the insect’s antioxidant defence systems, so that the mechanism of action is primarily attributed to oxidative stress, where it causes cellular damage and gradual death (Ziuzina et al. 2021).

However, further investigations are needed for the specific parameters for effective control of T. castaneum using DBD plasma. DBD is preferred because it is more efficient than other types due to the presence of a dielectric coating and generates a uniform, large-area discharge at atmospheric pressure, enabling continuous industrial processing unlike vacuum systems or narrow plasma jets. It also allows for in-package treatment to eliminate pests inside sealed products, preventing re-infestation while avoiding thermal damage to sensitive food items. Our research study is primarily aimed at determining if DBD cold plasma can serve as a viable, chemical-free alternative for managing this resilient pest in stored food products. To provide baseline efficacy data that can inform the development and optimisation of cold plasma technology is the awaited outcome for implementing it as a practical component of integrated pest management strategies for stored products. Considering the above aspects, this study aims to examine the efficacy of a DBD cold plasma system in inducing mortality in adult T. castaneum under different treatment conditions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Rearing of insects

Cultures of T. castaneum were maintained in a laboratory setting. Following standard protocols established in other studies, we had reared the beetles on a medium of organic whole wheat flour supplemented by a 5% (by weight) brewer’s yeast (Đukić et al. 2020; Visakh et al. 2022). The cultures were taken in glass jars covered with muslin cloth for ventilation and maintained under controlled conditions to ensure a continuous availability of insects for the treatments. For this study, we have ensured a test population of uniform 3-5-day-old adults, so that the adults that emerged over three days were collected and kept for an additional two days.

2.2 Cold plasma apparatus and experimental procedure

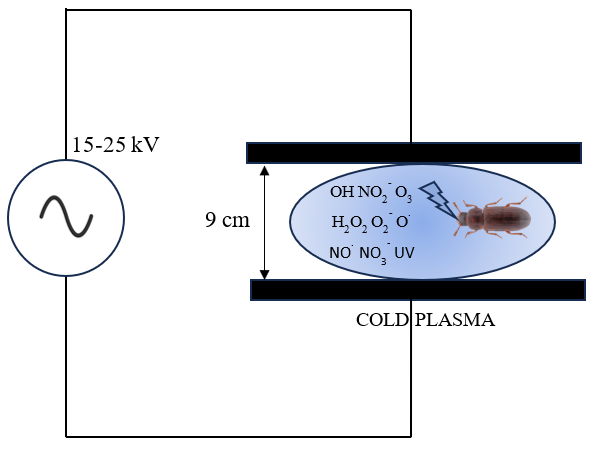

The cold plasma treatments were performed using a pin-to-plate type dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) unit operating at a frequency of 50 Hz, capable of generating up to 25 kV and a maximum power of 150 W, with a current load ranging from 0.3 mA to 2.8 mA. For the treatment, samples were placed on the lower electrode plate. There are four electrodes, each in one of the four chambers on either side of the machine (Figure 1). The electrode height can be adjusted from 7 to 10 cm as required. A five number of adult red flour beetles were placed in a 9 cm Petri plate for each treatment, and sealed by using a cling film (Figure 2). After that we had exposed the samples to cold plasma at three voltages (15, 20, and 25 kV) for three exposure times (30, 45, and 60 min) at a constant electrode height of 9 cm. A control group was maintained under identical conditions without plasma exposure. Each treatment was replicated four times. The experiment was performed under room conditions with a temperature of 30±2°C and a relative humidity of 70±5 per cent. The schematic diagram of the DBD cold plasma system setup is illustrated in Figure 3.

2.3 Data analysis

Following the treatment, adult beetles were monitored for mortality on the third, fourth, and fifth days. An insect was considered dead if it showed no movement when prodded. The percentage of adult mortality was calculated, and the data were analysed using a factorial completely randomised design (two factorial CRD) using GRAPES, which is an R-based statistical package (Gopinath et al. 2020).

3 Results

The effect of cold plasma on adult T. castaneum mortality in our study was significant over the untreated samples and directly correlated with applied voltage, exposure time, and post-treatment observation period. No mortality was recorded in any control groups.

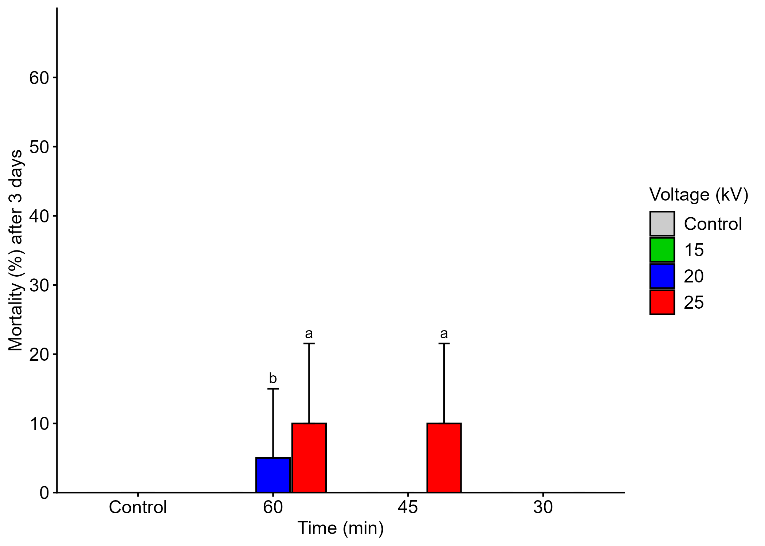

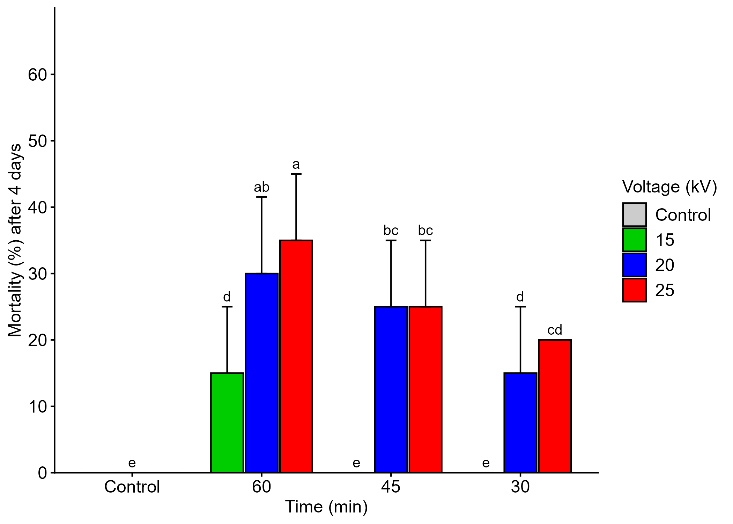

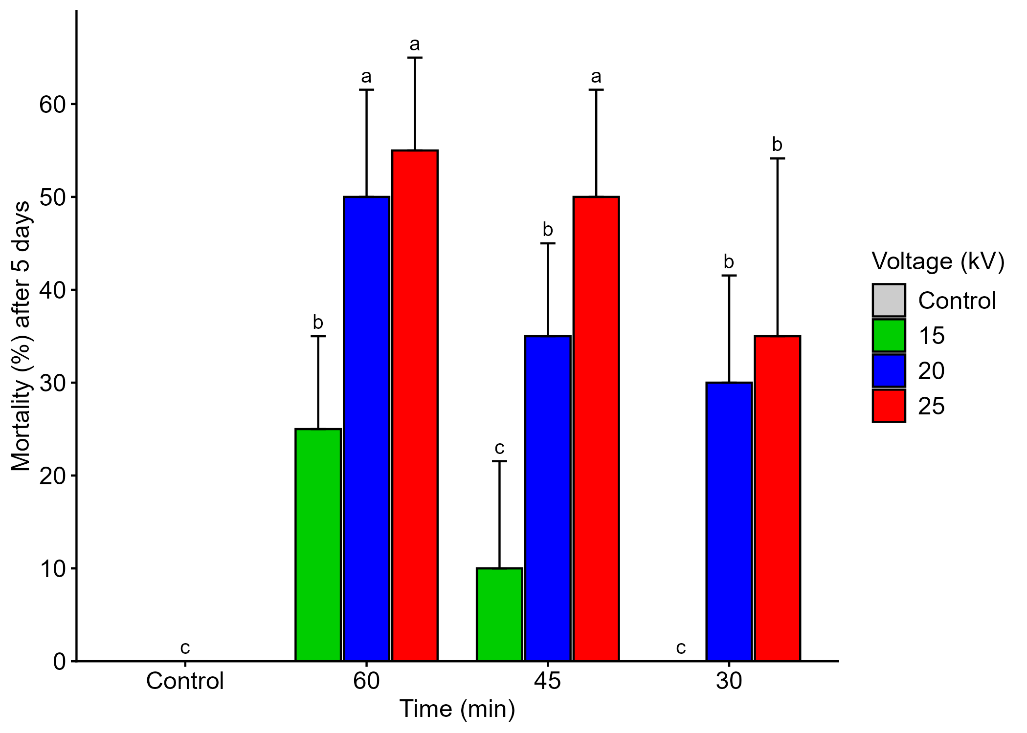

Mortality was first observed three days post-treatment, with the highest rate (10%) at 25 kV (Figure 4), it increased substantially by day 4 (35% maximum) (Figure 5). By day five, the mortality rates had significantly increased (Figure 6). There was a clear proportional relationship, where mortality increased with both voltage as well as exposure time. The maximum mortality of 55% was observed at 25 kV after a 60-minute exposure (Table 1). These results clearly show a dose-dependent relationship. For example, at 5 days post-treatment, increasing the voltage from 15 kV to 25 kV (at 60 min) raised mortality from 25% to 55%. Likewise, when we fixed the voltage to 20 kV, extending the exposure time from 30 minutes to 60 minutes increased the mortality from 30% to 50%. Conversely, the lowest treatment setting (15 kV for 30 min) resulted in 0% mortality across all observation days, confirming that treatment efficacy requires a minimum threshold of voltage and duration. The mortality percentage at higher different treatment combinations (25 kV-60 min, 25 kV-45 min, 20 kV-60 min) were found to be statistically significant from the lower combinations (p-value= 0). This delayed mortality suggests that the damage inflicted by the plasma’s reactive species initiates physiological and metabolic disruptions that lead to death over several days, a phenomenon also observed by (Ziuzina et al. 2021).

| Voltage (kV) | Electrode height (cm) | Time (min) 60 | Time (min) 45 | Time (min) 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 9 | 55 ± 10.00a | 50 ± 11.54a | 35 ± 19.14b |

| 20 | 9 | 50 ± 11.54a | 35 ± 10.00b | 30 ± 11.54b |

| 15 | 9 | 25 ± 10.00b | 10 ± 11.54c | 0 ± 0.00c |

| Control | 0 ± 0.00c | 0 ± 0.00c | 0 ± 0.00c |

4 Discussions

The mortality rates in this study, while significant, are lower than those reported elsewhere. For example, (Ziuzina et al. 2021) achieved 95-100% mortality of adult beetles. However, their experiment involved direct plasma exposure, which is more intense than the indirect exposure through a sealed Petri plate used here. In another study, (Ratish Ramanan, Sarumathi, and Mahendran 2018) reported 100% mortality across all T. castaneum life stages, but they used different plasma parameters and a lower electrode distance of 3.7 cm, whereas we used a higher distance of 9 cm. Plasma generation will be higher when the distance between the two electrodes is minimised (Jin et al. 2022). Similar results were also obtained in a study using Callosobruchus chinensis, which showed a complete elimination of the pest in chickpea under a shorter electrode distance of 3cm (F. Pathan, Deshmukh, and Annapure 2022; F. L. Pathan, Deshmukh, and Annapure 2021).

A study on rice weevil Sitophilus oryzae at a higher voltage of 80kV (much higher than the present study) for 5 min at 5cm electrode height reported only 60% mortality in adults. When the exposure time increased to 10 minutes, complete mortality was achieved (N. Kirk-Bradley et al. 2024). Research by N. T. Kirk-Bradley et al. (2023) indicated that a 100% mortality rate for adult Callosobruchus maculatus (Cowpea weevil) was achieved when specimens were exposed to a high voltage of 70 kV for 3 minutes, with an electrode spacing of 5 cm. A comparable mortality rate could be achieved by reducing the voltage to 2kV and narrowing the electrode gap to 3 cm, but this required an increase in treatment time to 24 minutes (Anbarasan et al. 2023). At a voltage of 24 kV a value very close to our study, but a lower electrode gap of 3 cm could obtain a complete mortality of adult rice weevil, S. oryzae when exposed for 30 sec under cold plasma (Than et al. 2024).

Oxidative stress is the major mechanism involved in the insecticidal action of cold plasma. The RONS generated by the plasma can degrade the insect cuticle by penetrating the body wall, thus causing severe damage to vital cells and tissues, as shown by reduced insect respiration rates and alteration in the antioxidant enzyme levels (Ziuzina et al. 2021). Other than these morphological and physiological damages, it can also cause other biochemical changes in insects, such as lipid peroxidation, increased concentrations of glutathione S-transferase (GST), and catalase (CAT) (Zilli et al. 2022). Significant increase in the activity of GST and CAT and also increased lipid peroxidation was noted in the insect P. interpunctella after cold plasma treatment which led to the severe larval mortality of 86% (Abd El-Aziz, Mahmoud, and Elaragi 2014). Ferreira et al. (2016) reported that cold plasma treatment in drosophila could cause abnormalities in the trachea which become curved and broken ultimately leading to the insect death. The same study also come up with another finding that this CP treatment can also affect the pigmentation and melanisation processes in the insects. Severe malformations in the reproductive structures were observed in the male red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus due to exposure under cold plasma (Mahmoud, Abd El-Aziz, and Elaragi 2015). These all morphological and physiological abnormalities after CP exposure can lead to the death of insects. Compared to other physical methods, cold plasma offers a residue-free alternative to fumigation and other chemical methods and does not involve ionising radiation or high temperatures, which can degrade food quality (Pankaj, Wan, and Keener 2018).

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrates the strong insecticidal effects of dielectric barrier discharge cold plasma on adult T. castaneum. The treatment potential is influenced by the applied voltage, exposure time, and post-treatment period, all of which have a significant impact on the mortality of the red flour beetle. The highest mortality rate of 55% was recorded after five days of treatment, at 25 kV and a 60-minute exposure and the lowest at 15 kV and 45-minute duration with a record of 10%, but no mortality could be observed at the same voltage with 30-minute exposure, which is same as the control value Our results show the potential of cold plasma as part of an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy for stored products, even though total mortality was not achieved.

6 Limitations and future line of work

Despite its potential, widespread adoption of cold plasma technology for pest management is hindered by several barriers. The scalability of this technology from lab to industrial level, along with the initial capital investment in the equipment, is the major challenge. Since the penetration depth of plasma is mostly restricted to the surface level, it makes it challenging to treat large amounts of stored grain efficiently. The effectiveness can also vary greatly depending on the type of plasma system we use, the life stage of the target insect, and the commodity matrix. It may also take a longer exposure period to produce a substantial mortality rate. The research should concentrate on overcoming these obstacles. The main goal is to create cold plasma as a residue-free, sustainable substitute for chemical fumigants and other thermal technologies. Research should focus on improving the instrument designs for efficient treatment with less power consumption, investigating synergistic effects by combining plasma with other techniques in Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies, and thoroughly evaluating its effects on the nutritional and sensory quality of treated food products. Further studies are needed regarding the plasma-commodity interactions that is how the CP affect the quality of the food products, cost analysis of the machine and its safety assessment.

References

Publication Information

- Submitted: 12 November 2025

- Accepted: 05 December 2025

- Published (Online): 06 December 2025

Reviewer Information

Reviewer 1:

Dr. Kaushik Pramanik

Assistant Professor

Swami Vivekananda University, West BengalReviewer 2:

Dr. Anu Thomas

Assistant Professor

College of Agriculture, Ambalavayal

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of the publisher and/or the editor(s).

The publisher and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

© Copyright (2025): Author(s). The licensee is the journal publisher. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits non-commercial use, sharing, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and no modifications or adaptations are made.